Older Haitian-Americans Eager To Vote Lean On Family, Poll Workers For Help

|

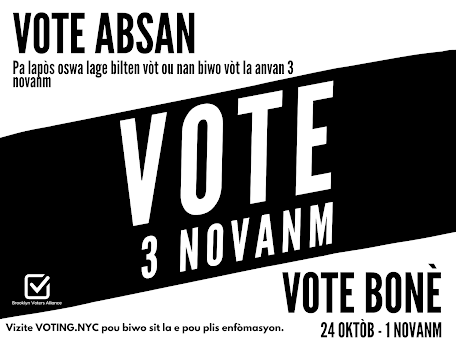

| A Creole flyer created by the Brooklyn Voters Alliance encourages people to vote in the upcoming election. |

Bienne Domand, a retired certified nursing assistant in Stamford, Connecticut, has not missed voting in a presidential election since she became a U.S. citizen in 2003. But while the 62-year-old grandmother of eight is always sure of her choice for president, she often leaves the rest of the ballot blank.

“When I don’t understand the ballot information or get confused, I go to the poll workers and say, ‘Can you point to the Democrat, the Blue one?’” Domand said. “I just want to know who they are and that’s all I need to know.”

Older Haitians, from the baby-boomer generation in their 60s and above, are among the most attuned to U.S. politics. For many, who fled Duvalier-era bloody elections that caused them not to discuss politics openly for fear of reprisal or death, being able to discuss and participate in U.S. elections is a civic duty they fill faithfully.

However, older Haitian-Americans struggle with several unique barriers when it comes to casting their ballots. Language translation is consistently viewed as the biggest obstacle hindering these senior citizens from fully participating. Other issues include information inundation, the layout of the ballot and, this year in particular, adjustments made to the voting process due to COVID-19.

As a result, with Nov. 3 rapidly approaching, Haitian-Americans are more attuned to the needs of senior community members whose votes are so crucial. Translating ballots into Creole is not enough, community members say. They also need support with the logistics of the process and to have clear explanations of items beyond the presidential nominees, such as the state and local races and legislative amendments.

Even in Florida, which has extensive language translation assistance, there are smaller logistics of voting that activists say older Haitian-Americans need to know.

“Miami-Dade County has workers providing language assistance at the polls, but it’s tricky because they will only know that you need language assistance if you check a box when you register,” said Léonie Hermantin, Director of Communications at Sant La Neighborhood Center. “Even though it’s in Creole, people who have literacy and language issues overlook that little box in the corner, which is barely visible.”

Help with language and logistics

Many are taking steps to provide direct and simple translations to help older voters successfully cast their ballots.

“We’re giving election information to the elderly Haitian community in plain Creole and we’re really keeping it as simple as possible,” said Stanley Neron, a community advocate in Elizabeth, New Jersey. “You don’t want to utilize the original linguistics of the ballot because it will get too complicated and you will lose them.”

Stanley Neron works with churches in Elizabeth, NJ to help older Haitian-Americans learn how to vote. Photo courtesy of Stanley Neron.

Neron and others are working extensively with the faith-based community in Elizabeth by creating videos in Creole and sharing it with pastors of different churches. The videos contain information on how to place and seal the ballots into envelopes, where to put names and addresses, and the importance of returning ballots earlier than the day of the election.

“With this election, we definitely have more people registered to vote than four years ago but they have no understanding of what the ballot means,” said Sheenaider Guillaume, a Linden, New Jersey resident. “What we’ve especially come across is that they don’t understand there’s a backside to the ballot and they don’t understand who to vote for outside of the presidential election.”

If older voters do not fully understand the process or properly complete ballots, their lack of participation could negatively affect Haitian-Americans as a bloc.

Jan Combopiano, senior policy director at the Brooklyn Voters Alliance, said this is why organizations such as the New York City Board of Elections must do more to improve language access. She said the state needs to implement legislation and allocate more money to provide voting resources in languages besides English.

“We want people to make informed choices when they vote and language should not be a barrier to people voting,” Combopiano said. “Any time anyone gets dissuaded because there’s no one to help them, this might mean they’re not going to vote in the future and they could be sending a message to the rest of the people in their family that voting is not important.”

In battleground Florida, Haitian-American politicians and advocates are proactively working to ensure the older population gets the help they need before the election.

Dotie Joseph, a Florida House of Representatives member whose 108th District is heavily Haitian, has been explaining on Haitian radio what the ballot amendments are and answering questions about them from Haitian-Americans in Creole.

“The ballot amendments and voter education are necessary across the board and it’s even more pronounced in any immigrant community, especially when there’s a language barrier,” Joseph said. “In addition to this language barrier, a lot of these folks are just intimidated by the whole voting process and they need somebody there to assist them.”

Help from family and friends

Some Haitian-Americans see their older family members struggling with a mountain of election-related mail and have become concerned about information overload on their behalf.

“My parents receive so many requests for mail-in ballots and are being flooded with information,” said Lana Joseph, an Atlanta-based attorney.

Joseph’s 74-year-old mom speaks only Creole, while her dad, who is 78, speaks English but needs assistance with complex topics. When Joseph recently visited them in Stone Mountain, Georgia, she explained to them that the mail they had received was not a ballot, but a form to request a ballot. After they successfully received their ballots, she sat down with them and had a conversation about the candidates and the issues so they could fully understand.

Joseph said that if older Haitian-Americans do not have family members who can assist them with understanding how to vote, they might not even try to seek help.

And with COVID-19 curtailing opportunities to socialize, some older Haitian-Americans may put the election on the backburner.

“We are not able to see them face-to-face anymore at events and if they have family members who are not at home helping them, it is even more frustrating than before,” said Joseph, 41. “They cry out for help, but we might not be able to get to them because they’re in their home.”

For Domand, the Connecticut septuagenarian, the best way to ensure she is able to cast her ballot is by voting in-person. This year, she said she plans to have her son go to the poll with her because she wants her vote to count.

“There’s anxiety around this election because they’re hoping that their votes count, that people are not stealing the ballots or discrediting the ballots,” said Domand. “I can’t wait to go in person and vote Democrat.”

This article was originally published in The Haitian Times.

Comments