Federal law excluding Creole translation burdens New York’s Haitian voters

This article is the fourth in a series about the 2022 federal midterm and state elections, supported by the Center for Community Media at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. The first three installments looked at the Haitian-American legislative caucus in the NYS Assembly, how the caucus could change if more Haitians were elected to office and how the issue of affordable housing in Flatbush could mobilize Haitian voters to head to the polls.

NEW YORK — Every election season, Sabine French goes out of her way to assist fellow Haitians who want to vote. She goes with four of her family members to the polls and breaks down each portion of the ballot for them, line by line.

Nevertheless, she said the weeks leading up to Nov. 8 are extremely taxing for her, due to the high demand for assistance with voting. In the Haitian enclave of Cambria Heights, Queens, she said her frustration mounts when she sees that no official Creole-speaking translators are present.

“I’m happy that I have a relationship with the community, but every election season, I’m bombarded with calls from Haitian immigrants seeking information,” said French, Queens Borough Advocate at the Office of the New York City Public Advocate. “They want to know where the polling site is, who the candidates are and the hours for voting because they want to participate, but they’re unable to find the information.”

Haitian residents comprise 2.6% of New York City’s foreign-born population, according to a report from the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA). The report states that 78,250 Creole speakers live within the five boroughs, making Creole the fifth most common non-English language spoken.

|

|

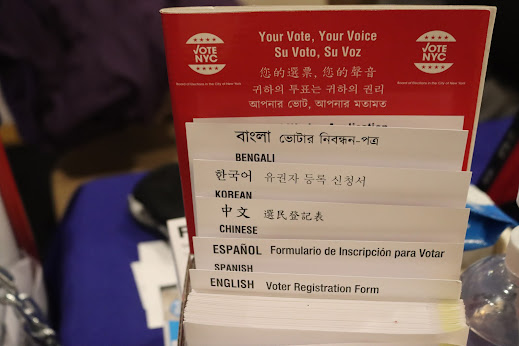

| Voter registration forms available in five languages – English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean and Bengali. Taken at an early voting site, Antun’s, at 96-43 Springfield Blvd. in Queens Village, New York City. Taken on Sunday, October 30, 2022. (Emily Sauchelli for The Haitian Times). Creole translation efforts in NYC The New York City Civic Engagement Commission (NYCCEC), using demographic datafrom the federal census, mandates that Creole-speaking interpreters be present at the poll sites. But, it does not allow interpreters to accompany voters inside to guide them through the ballot, particularly the back side. Members of the Commission said that creates a problem. “When there are a ton of back referendums and all of this language that the common person doesn’t understand, they have to go seek guidance,” said Debbie Louis, Creole language ambassador for the Commission’s Language Assistance Advisory Committee and a senior advisor at the New York State Assembly. “This is a very challenging situation where I see people who are discouraged to vote,” Louis said. “We use all of the data from the CEC to prepare us for the tables that we’ll use in specific election districts where we know folks will need language access.” In particular, Louis works on translating voter registration forms, posters on voting information and civic engagement materials into Creole. She also seeks to have them distributed physically in schools and virtually over social media. In September, Louis said, the CEC approved an ad campaign to run on Haitian radio stations and TV networks about the importance of voter engagement in the general election. Through the Language Access Plan, the commission allocates interpreters at poll sites based on the most common languages spoken in specific neighborhoods. In addition, they create advertisements in community and ethnic media, informational videos, and brochures and flyers for canvassing. MOIA has also outlined how it works to expand language access to non-English speakers. That includes providing translation services for a multitude of city agencies, including with the Campaign Finance Board (NYCCFB) to strengthen language accessibility in elections. In 2017, MOIA began overseeing the city’s official language access law (LL30) as well as the resources and programs needed to assist non-English speakers. Yet, these efforts, while numerous, apparently aren’t reaching many residents who need the services. “We know in a city where everyone speaks a second language that voting outreach and recruiting efforts should be greater,” said French. “I don’t think that it’s because of a lack of qualified translators. I think it’s not meeting them where they’re at.” Inside view of the early voting site. Taken at Antun’s, a catering hall that also is serving as an early voting site, located at 96-43 Springfield Blvd in Queens Village. Taken on Sunday, October 30, 2022. (Emily Sauchelli for The Haitian Times.)Plans for next year & beyond Going forward, voting rights organizations said the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act in New York State is the right direction and will hopefully expand increased voter outreach in languages like Creole, as well as allowing interpreters to accompany residents to the voting booths. “The Board of Elections won’t even allow translators inside the poll site, voters are forced to be outside and this is an example of something that is hurting them,” said Jan Combopiano, Senior Policy Director for the Brooklyn Voters Alliance. “Hopefully, we’re on the cusp of big transformational changes with the new state voting rights act.” Groups like the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) have provided resources to eligible voters to learn more about how they can participate in elections through a voting hotline, as well as info on how to report voting rights violations. “The important thing that language assistance does is that it welcomes communities, especially communities that don’t necessarily feel welcome in our democracy as an initial impulse,” said Perry Grossman, Supervising Attorney at the NYCLU. “When you see election communication, signage and advertisements in your native language, it’s a sign that they want you participating, that you’re welcome here and they want you to be a part of this civic engagement.” This article was originally published in The Haitian Times. |

Comments